Working with broken mental models

Finding common ground between Nassim Nicholas Taleb and Alan Watts

I just finished reading The Black Swan by Nassim Nicholas Taleb (NNT), and I suspect it will be the best non-fiction book I'll read this year. It’s part behavioral economics, part statistics, part finance, and part philosophy.

For those of you unaware, the book explores the many facets of how and why, we, as societies and individuals, fail to understand randomness and are particularly bad at preparing for large deviations (so-called Black Swan events).

As put by NNT, a Black Swan event has three characteristics:

rarity, extreme impact, and retrospective (though not prospective) predictability.

Reading about Black Swans feels especially relevant in 2020/21. But one could also argue that the pandemic, the capital riots, and the blackout in Texas are not (pure) Black Swan events because they were predicted by some people.

In practice, though, it doesn't really matter if some people predicted a Black Swan as long as the event catches enough people off-guard to have an outsized impact (e.g., the subprime mortgage crash in 2007/08).

So, what are some of the reasons why people are prone to Black Swans? Here are a few reasons NNT presents in the book that stuck with me:

The “Problem of Induction.” When do our observations become facts? For example, the book’s namesake, the black swan — once it was discovered “down under” — disproved the longstanding notion that “all swans are white”

Our innate need to establish cause and effect (create a story) can result in misattribution or oversimplification

Our inability to conceptualize real risk. Real risk is not like the risk found in a casino, where the odds are known

Our tendency to platonify, or impose mental models onto reality

This last one — tendency to platonify — is of particular interest to NNT, who spends much of the book grilling the deficiencies and over-assumptions found in Modern Portfolio Theory and much of the social sciences.

There is nothing inherently wrong with creating models to understand the world, but it’s easy to become arrogant in their efficacy, particularly when they’re backed by calculations and “math.” It also doesn’t help that language, education, and other systems around us can reinforce these models and make it difficult for others to re-evaluate their truthfulness.

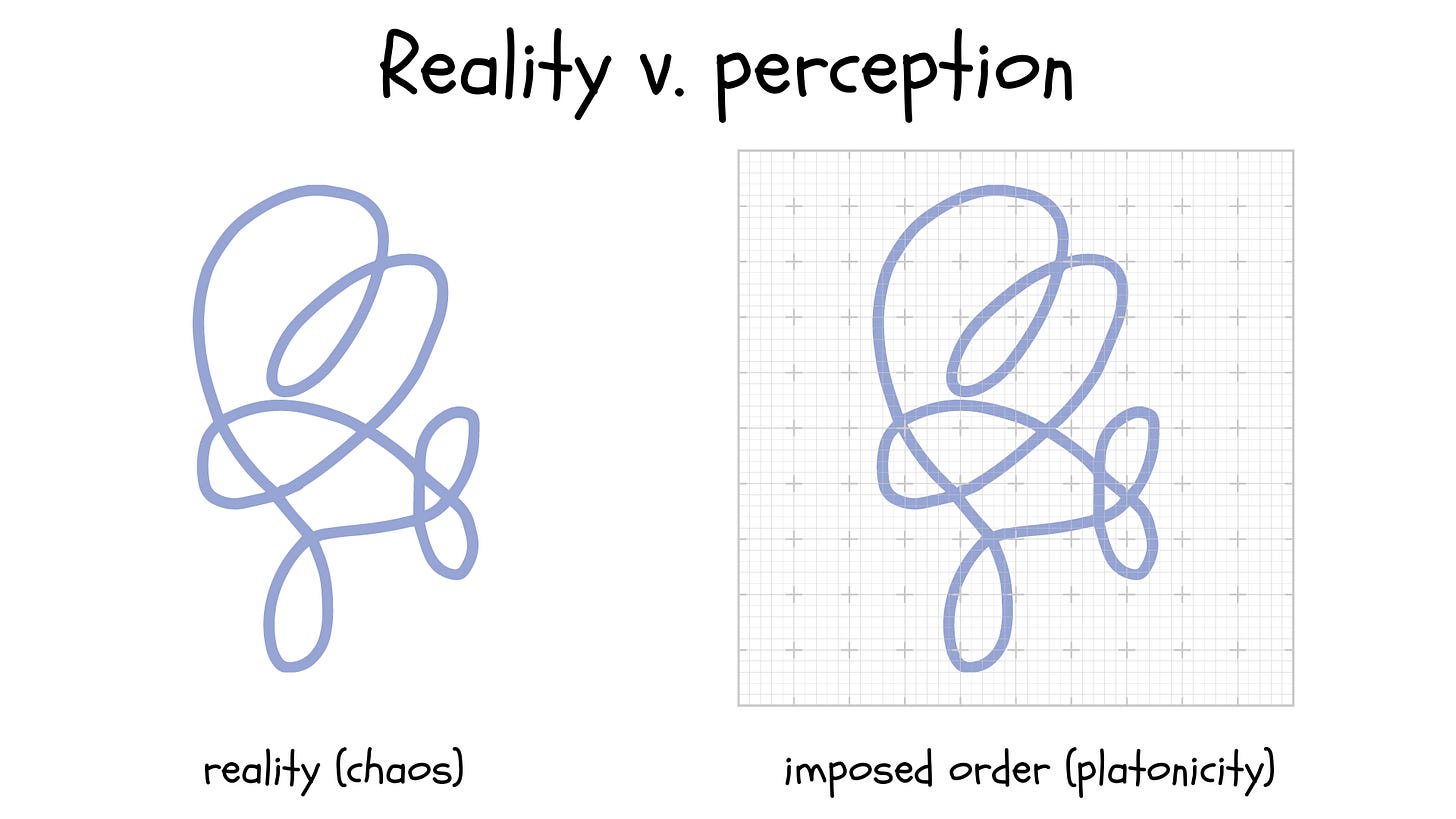

NNT’s discussion of the false security afforded by “knowledge” reminded me of a similar discussion that takes place in Alan Watts’ The Book: On the Taboo Against Knowing Who You Are. There's a moment where Watts' describes the world as wiggles that have no discernable end or beginning in space or time.

They wiggle so much and in so many different ways that no one can really make out where one wiggle begins and another ends, whether in space or in time.

However, if you drop a grid over the wiggles, as shown below, suddenly the wiggles look like something that can be analyzed and understood.

Perhaps the wiggles in the grid can be understood in some capacity, but we need to be able to admit that its possible for the wiggles to escape our grid. To deny that and say “the wiggles can only take place within the grid I drew” would be to platonify.

In The Book, Watts’ uses this illustration to demonstrate how the separateness we feel between ourselves (our sense of self) and the rest of the world is an illusion.

But it is always an image, and just as no one can use the equator to tie up a package, the real wiggly world slips like water through our imaginary nets.

Where Watts' speaks to how our mental model of "self” leads to unhappiness, NNT talks about how arrogance in our mental models can lead to financial (practical) ruin.

It pays to be skeptical. Doing so means having to learn how to live with uncertainty.