On the Pain of Writing

What to do when pursuing your passion hurts

Telling myself to write is the best productivity hack I've ever discovered. Suddenly, my apartment is vacuumed, my taxes are done, and I've even called my grandmother.

These rituals of productive procrastination make me a great housekeeper, but when all those tasks are said and done, I have little to no time left for writing. It’s especially dangerous because with this tactic, I temporarily bamboozle myself into feeling like I’ve done something meaningful. That I have my shit together and life just got in the way of my writing.

Obviously, there's a lot of cognitive dissonance and self-sabotage here. During the day, I keep a journal of story ideas, I make character notes when inspiration strikes, but come the time to put words to the page, scrubbing the toilet suddenly feels like the most urgent and intoxifying project in the world. Staring at a blank page, I find myself yearning for a whiff of Clorox.

Understanding procrastination

A few months ago, late into the night and deep in the YouTube rabbit hole, I stumbled upon an interview with Gabor Mate, the Canadian physician and addiction expert.1 What stood out in particular to me was this question he posed: what does the compulsion allow the addict to avoid?

For example, we may discover that through their addiction, the homeless fentanyl user avoids the reality of their material condition, the obsessive sports gambler escapes the reminders of his ex-wife's infidelity, or that the workholic evades incessant thoughts of unworthiness.

And in the vein of that discovery, I asked myself, why do I have these compulsions not to write?

Role of “the gap”

The answer, I uncovered, is that writing for me is a painful process. I think this discomfort can be best described by Ira Glass's quote regarding "the gap."

All of us who do creative work, we get into it because we have good taste. But there is this gap. For the first couple years you make stuff, it’s just not that good. It’s trying to be good, it has potential, but it’s not. But your taste, the thing that got you into the game, is still killer. And your taste is why your work disappoints you. A lot of people never get past this phase, they quit. Most people I know who do interesting, creative work went through years of this. We know our work doesn’t have this special thing that we want it to have.

But why is this writing gap so painful for me, in particular? For example, I like pottery and art, I can recognize good pottery and art, yet I'm perfectly content slopping away on a paint-by-numbers kit without worry. Obviously, I perceive a gap, but it doesn't bother me. Hell, I can bang out my company’s internal newsletter in an hour too, so why not my own personal work?

The answer is a bit simple and silly, but it wasn't obvious to me for a long time.

I had simply staked too much of my identity and self-worth around "being a writer."

A company newsletter is a job that needs to be done and not something someone typically earns acclaim for, so it's okay for it to not be 👏 great 👏. I'm not at all concerned with becoming a visual artist, so not being good at pottery or painting isn't a reason to worry either.

But I would like to publish short stories, maybe even a novel some day.

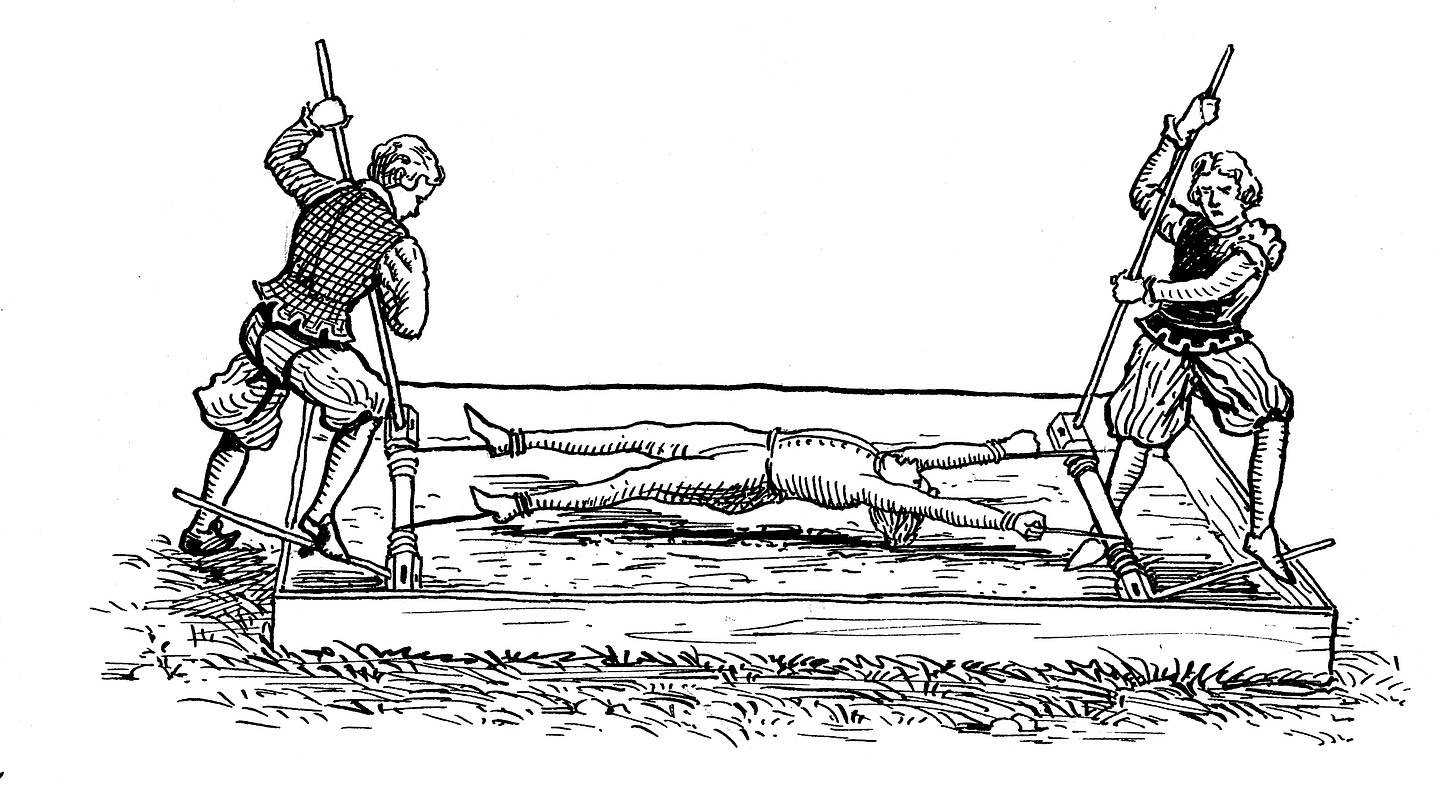

So whenever I'd have to face a first-draft, or re-write a story, the stakes were incredibly (and unnecessarily) high. Every evening I'd sit myself down in front of the keyboard, it’d wrench my ego in the existential equivalent of spending a night on the rack.

My work was no longer about the piece, but about proving to myself that I am in fact capable of being a great writer. And when faced with the reality that my work wasn’t as good as I’d want it to be, I was opening myself to indulge my worst self-criticism. And I know I'm not alone.

This is exactly what Steven Pressfield warns about in The War of Art, where he describes "The Resistance" – a metaphor for all the things that stop us from doing our creative work.

"[The Resistance] wants us to stake our self-worth, our identity, our reason-for-being, on the response of others to our work"

Seeing creative work as a measure of your worth adds an unnecessary burden to an already fragile process, and more importantly, zaps the fun out of it all. As Rick Rubin describes in The Creative Act, we do our best work when it retains an element of play.

Active play and experimentation until we’re happily surprised is how the best work reveals itself.

So what can we do?

Glass suggests we can close the gap by chipping away at it and letting ourselves go through the cycles.

It is only by going through a volume of work that you will close that gap, and your work will be as good as your ambitions. And I took longer to figure out how to do this than anyone I’ve ever met. It’s gonna take awhile. It’s normal to take awhile. You’ve just gotta fight your way through.

There’s power to repetition of course when it comes to developing skill –we can look at the oft-cited pottery example2 – but I think an underlooked aspect of repetition is how it naturally lowers the stakes.

If someone aspires to be a great writer, investor, artist, or whatever, and they systematically do that thing at some regular frequency, then that means that there is no one story, no one investment, no one painting that will make or break their career. The work right in front of them becomes just one of many instances and the pressure to get this one "just right" is diminished. However, this does require having trust in yourself that you will pick this up again and work at it consistently.

If I run three times a week, I'm okay with having a bad day once in a while, because I know I'll give it another shot this weekend. What's most important is to show up to give myself the opportunity to do good work.

The most meaningful way we can lower the stakes, however, is to become comfortable with ourselves as we are. Or rather, accept where we’re at. If we can feel whole right now without the achievement, then there's no reason to do the work but for the pleasure of completing the work itself.

Reaching this state can be difficult, given that we're taught to look up to those who do extraordinary things. I think it can be useful, though, to realize that the status we desire or the achievement we wish to notch into our belts isn't going to provide long-term happiness. I think this is a realization many people discover as they get older and start to reach those "life milestones" that were so hyped up to them when they were young.

It's well documented that our happiness is multi-factorial, and there isn't one shortcut that let's you skip over all that complexity (see the hedonic treadmill3 and the arrival fallacy4). Things aren't that binary and that's a good thing.

So to wrap things up, if you're like anything like me, there's three parts to getting over that fear of doing the work.

1. Detach your self-worth from the outcome

2. Do the work regularly

3. Do what you can to fall in love with the process

I can't claim to have all these things right myself, but I find solace in the fact that the heap of laundry in the corner of my room isn't as enticing as it once was.